An essay submitted to the Faculty of Education and Arts at Nord University in conformity with the requirements for the Queen’s University International Alternative Practicum credit, administered by the CANOPY Project

May, 2021

- In Partnership with Nord University & The CANOPY Project

- Supervisors: Dr. Wenche Sørmo, Dr. Karin Stoll & Mette Gårdvik

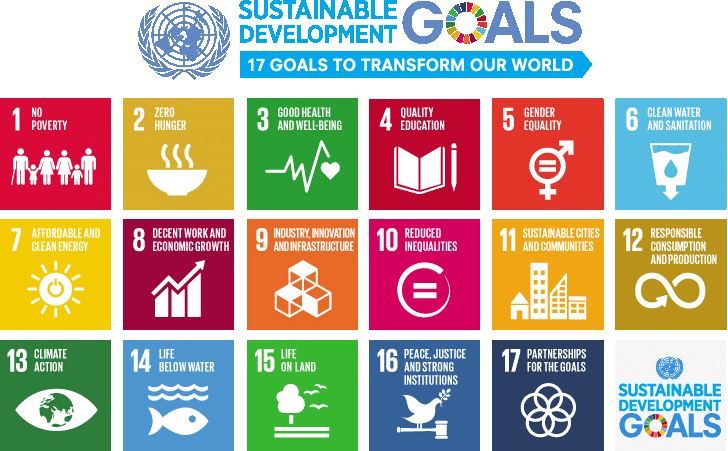

As our society continues to advance in its ways of living, we often forget the implications we have on our planet. In any case, understanding what sustainable development entails is important for the sustainability of our environment and community. As such, this addition to the CANOPY project will look into the development of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in both Ontario and Norway while also delving into place-based education (PBE). Thanks to the collaboration between Queen’s University in Canada and Nord University in Norway, a comparative study will be done on the past and current education systems of both countries in relation to sustainability and sustainable development. In order to further understand the difference and the presence of ESD in both regions of this study, the following question will be answered: “What does Education for Sustainable Development look like in Canadian and Norwegian education society?”

To gain a full understanding of what this research encompasses, exploration will be done on the difference between sustainability, Environmental Education (EE), and Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). In addition, there will be further inquiry into EE and ESD within the Ontario and Norwegian school systems and curricula, factors that influenced the integration of ESD, and teaching practices that currently exist and are popularized in both geographic regions. Through the use of qualitative data (e.g., interviews and surveys), further research has been done on the various perspectives that teachers in Ontario and Norway hold when it comes to their knowledge and experience of ESD.

In summation, Ontario and Norway differ when it comes to implementing ESD in their respective educational systems and curricula. Through various research papers and interviews used to support this research, Norway in particular puts emphasis on ESD and EE due to cultural, political and social factors that dictate the importance of taking care of the local environment. However in Ontario, ESD is still an emerging concept for both schools and educators within the Ontario education system. That being said, incorporating ESD within Ontario curricula has become increasingly popular over the years amongst educators and students alike. Throughout this work, similarities and differences of incorporating ESD within Ontario and Norwegian school systems and curricula will be further discussed in conjunction with experienced and new teachers’ perspectives on ESD.

The CANOPY Project (Canada-Norway Pedagogy Partnership for Innovation and Inclusion in Education) is a program built from the partnership between the Norwegian Agency for International Cooperation and Quality Enhancement in Higher Education (DIKU), the Faculty of Education and Arts at Nord University in Norway, and the Faculty of Education at Queen’s University in Canada, as shown in Appendix I. Thanks to the support of schools situated in Nordland, Trøndelag and across Ontario, educators can gain a better insight to our current education system from a “holistic and international perspective” (CANOPY, 2021). By partaking in this major project, popularized topics and issues within the world of education are further examined. As such, the focus of this study will be on the development of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in both Ontario and Norway while also delving into place-based education (PBE). More specifically, answering the question: “What does Education for Sustainable Development look like in Canadian and Norwegian education society?”.

For this study, it is imperative to gain a better understanding of both the Ontario and Norwegian school systems. In Ontario, the public school system is essentially divided into two main stages: elementary school for those ages 4 to 13 (i.e., kindergarten to grade 8), and secondary school for those ages 13 to 18 (i.e., grade 9 to grade 12). Within an Ontario elementary school, students only have one teacher who teaches all subjects required by the Ministry of Education. Then once students attend secondary school, they take classes based on subjects in which individual teachers specialize. Unlike Ontario, the public education system in Norway is divided into three main stages: primary school known as Barneskole (for those ages 6 to 13), lower secondary school known as Ungdomsskole (for those ages 13 to 16), and upper secondary school known as Videregående skole (for those ages 16 to 19) (Study in Norway, n.d.). The primary and lower secondary schools utilise the same curriculum, whereas the upper secondary schools have “vocational subjects and specializations” similar to Ontario (Study in Norway, n.d.). With this basic information in mind, ESD within the Ontario and Norwegian education system will be better understood.

Introduction to Sustainable Development

Based on various articles, it has been indicated that there is a notable difference between the words ‘sustainability’ and ‘sustainable development’. However, we often see the two words being used interchangeably. According to a UNESCO webpage on sustainable development: “Sustainability is often thought of as a long-term goal (i.e., a more sustainable world), while sustainable development refers to the many processes and pathways to achieve it (e.g., sustainable agriculture and forestry, sustainable production and consumption, good government, etc.)” (UNESCO, 2015). An additional defining feature of sustainable development includes the fact that it intertwines four specific dimensions of our current world: the society, the environment, the culture, and the economy. For the purpose of this study, both sustainability and sustainable development will be examined; however, emphasis will be put on Education for Sustainable Development (ESD).

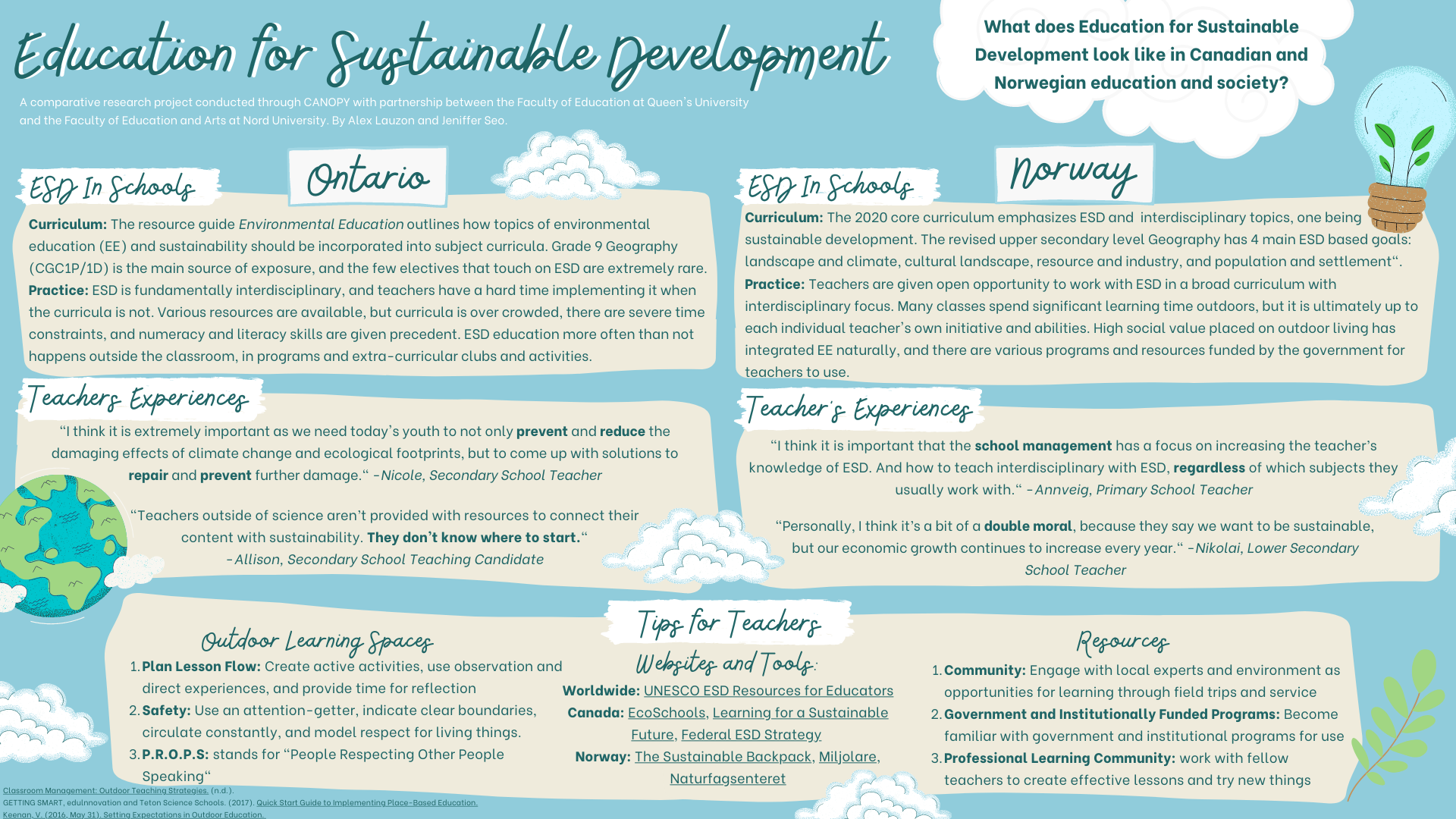

The concept of sustainable development was initially introduced and popularized during the United Nations (UN) conference held in Rio in 1992 with the help of the World Commission on Environment and Development, also known as WCED (Sætre, 2016, p. 66; Sauvé, 1996, p. 9). Since then, there has been an increased awareness of implementing sustainable development into current teaching practices in both Ontario and Norwegian schools. The UN even declared 2005 as the start of the “decade for Education for Sustainable Development”, also known as the “decade of action” (Nayar, 2013; United Nations, n.d.). In support of this motion, the UN created and implemented the Sustainable Development Agenda which includes seventeen sustainable development goals that will help the world “achieve a better and more sustainable future for all” (United Nations, n.d.). To gain a better sense of what each of the seventeen goals are, an illustration has been included below (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals from “Sustainable Development Goals” by the UN, 2015. Copyright [2015] by the United Nations.

In reality, there has been a growth in the presence of sustainable development; mainly in the hopes that countries will work together to solve issues that not only affect the environment but our wellbeing as well. By finding solutions to the overconsumption of food and water, to the over-extraction of materials, to the pollution occurring on land and in water, to poverty, to gender equality, and many others, it will be possible to make our world sustainable. According to an article on the Importance of Education for Sustainable Development written by Ajita Nayar (2013), who is a project manager for the Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) program at the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), ESD helps integrate “key environmental challenges like climate change into core subjects like math, science and art”. With this in mind, sustainable development is a pressing topic that should be increasingly addressed in schools, especially when everything at its core begins with education.

Environmental Education vs Education for Sustainable Development

With the popularization of sustainable development, there has been an increased presence of teaching about the environment and sustainability in schools across Ontario and Norway. Reading through various articles, two forms of education were prominent in the field of teaching environment and sustainability: Environmental Education (EE) and Education for Sustainable Development (ESD). According to the Ontario elementary curriculum for Environmental Education, EE is described as “education about the environment, for the environment, and in the environment by learning about the earth’s physical and biological systems, the dependency of our social/economic systems on natural systems, environmental issues, and positive/negative consequences on the environment created by humans” (OME, 2017, p. 2). Whereas ESD is referred to as “the integration of key sustainability issues into teaching and learning to provide opportunities for young people to acquire first-hand experience in addressing the socio-ecological challenges faced by their communities” by UNESCO (2017, p. 10).

In line with the definitions, EE and ESD have several key differences between them. For one, EE includes a broad spectrum of topics related only to the natural systems found in our world as well as the environmental issues caused by humans. As such, EE focuses on the “what”, “where” and “why” but not exactly on the “how” (i.e., how can we change our ways, how can we help the environment, and how can we change people’s minds and/or perspectives). Furthermore, EE is an older concept that is slowly being replaced by ESD. As indicated by Sauvé (1996, p. 9), an associate professor for the Faculty of Education at University of Quebec in Montreal (UQAM), “the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization even proposed sustainable development as the ultimate goal”, therefore suggesting environmental education to be “reoriented or reshaped”. The shift from EE to ESD comes from the fact that ESD focuses on the current issues that are affecting our communities and finding solutions to create a sustainable world (environmentally, socially, culturally, and economically). So, not only does ESD delve into the “what”, “where” and “why” of environmental issues and sustainability, but also the “how”. Independently, ESD can be viewed as an educational approach that was created for the earth’s and future generations’ well-being. For this reason, it is paramount for ESD to be incorporated into Ontario and Norwegian school systems and curricula.

EE and ESD within the Ontario school system and curriculum

Since the UN conference in Rio in 1992, the education system in Ontario has been slowly implementing EE and/or ESD into their curricula. For elementary schools, a resource guide titled Environmental Education was published by the Ministry of Education (UDIR, 2017). Based on grade levels, the document gives suggestions on ways in which EE could be incorporated into all subjects, including: drama, music, visual arts, French (core and immersion), physical education, language, math, native languages, science and technology, and social studies. When it comes to secondary school, students are mainly exposed to EE and sustainability in the mandatory Grade 9 geography course (course code: CGC1P/CGC1D). However, geography teachers are only required to teach sustainability during two strands of the course: during strand C when students look at managing Canadian resources and industries, and during strand E when students look at liveable communities in Canada (OME, 2018, p. 78-84). Additionally, there is an optional course that upper year students can take, titled “Living in a Sustainable World” (course code: CGR4E). The goal of this course is to examine the impact of human activity on our natural environment while also being aware of what can be done at home, at school, and in public to mitigate human’s impact on the environment (OME, 2015, p. 279). To give a general idea of what the course entails, some of the topics include: human impacts on ecosystems, sustainability of natural resources, and community action.

Even though a small presence of EE and sustainability exist within Ontario curricula, it is ultimately up to teachers to decide how much of EE and sustainability they would like to incorporate in their lesson plans. Based on the description of CGC1P/CGC1D, this mandatory geography course focuses on the physical and human geography of Canada and answers the question “what is where, why there and why care”, but misses the “how” (i.e., how can we change our ways, how can we help the environment, and how can we change people’s minds and/or perspectives). However, an examination of whether or not the current Ontario school system supports ESD will be further discussed later on. In addition, it is important to note that courses such as CGR4E are extremely rare. This is due to the fact that upper-level geography courses are all optional and can only occur if and only if there are enough students who are interested and if there are teachers who are willing to teach the courses.

Lastly, there are a number of key institutional elements that contribute to and have a role in implementing EE in Ontario. For instance, the existence of the Ministry of Education, which helps administer provincial law and policy that help with the growth of EE. In addition, policy activists such as Environmental Education Ontario (EEON), the Canadian Network for Environmental Education and Communication, the Council of Outdoor Educators of Ontario (COEO), the Ontario Association for Geographic and Environmental Education (OAGEE), and the Ontario Society for Environmental Education, all helped produce the most change in integrating EE in schools (Bardecki & McCarthy, 2020, p. 118). Of course, there are also school boards and trustees which have made progress in incorporating environmentally sustainable practices at the board-level such as EcoSchools and Energy W.I.S.E (Bardecki & McCarthy, 2020, p. 119). With the support of these institutions and organizations, EE and ESD can have a larger presence within the Ontario school system and curricula.

EE and ESD within the Norwegian school system and curriculum

Unlike Ontario curricula, primary and lower secondary schools in Norway utilize a core curriculum that includes core values and fundamental approaches for all grades and levels. Upon analyzing the curriculum, it was noted that there is an emphasis on providing hands-on learning experiences to the students. In addition, when it comes to core values and principles related to the environment and sustainability, there are three: (1.4) “the joys of creating, engaging and the exploring”; (1.5) “having respect for nature and environmental awareness”; and (2.5) “including interdisciplinary topics such as sustainable development in various disciplines besides natural and social sciences” (UDIR, 2020). Moreover, according to Særtre (2016), the Norwegian school system used to have three levels of approach to EE. The first and lowest level being “EE limited to learning about scientific knowledge”, the second approach being “EE based on learning about scientific knowledge but with specific goals to help develop environmentally friendly values and attitudes”, and the last approach being how our society causes environmental problems and knowing what to do to resolve conflicts surrounding sustainability (i.e., ESD) (Sætre, 2016, p. 68). By integrating these three levels of approaches to EE, teachers in Norway had the chance to cover topics that pertained to ESD. However, was there and is there still a large presence of EE and ESD in Norwegian school systems and curricula?

Before the Rio conference, primary schools merged social studies and sciences together to create a course called “Orientation” for grades 1 to 3. Once students were in grades 4 to 9, geography was a separate subject included within the social studies discipline alongside history and social sciences (Sætre, 2016, p. 70). After the Rio conference, social studies was then split into three different syllabi: geography, history, and social sciences. One of the main goals for the new geography syllabus related to EE, which included topics such as environmental balance between human and nature, pollution, recycling, poverty, and many others. In terms of incorporating EE and ESD in Norwegian primary school systems, there was a study done on Flaktveit School, a primary school located within the Municipality of Bergen. This particular school is known for its focus on ESD and ensuring that all their students are aware of the importance of sustainability. Additionally, Flaktveit collaborates with external sources to create immersive opportunities for their students. Some of the companies the school worked with included: BIR, a waste management company in Bergen; IKEA, where students learned about a large company’s role in solving environmental issues; and UNICEF, where students worked together to increase bike usage or find alternatives for local waste disposals (OECD, n.d., p. 4). Thanks to schools such as Flaktveit, other educational institutions throughout Norway are doing similar programs and collaborations due to the emerging importance of ESD.

Similar to the Ontario secondary school system, geography is a one-year compulsory course for students in upper secondary schools in Norway. Alongside geography, upper secondary students are required to take a natural science course for a year. In this course the environmental perspective is primarily ESD focused, with the intensity varying depending on the student’s subject focus (UDIR, 2020). Before the Rio conference, the curriculum created in 1976 “was the first general core curricula to state the importance of EE” (Sætre, 2016, p. 70). As a result, the geography curriculum was divided into two parts: cultural geography and physical geography. Unfortunately, environment and sustainability still did not have a prominent place within the course; however, they were covered in cultural geography through various topics related to environmental protection, community development and industrialization. Once the conference in Rio took place, changes were made to the main objectives in the geography curriculum. Instead of focusing purely on cultural and physical geography, it was crucial for the new curriculum to include environmental issues and sustainable development as one of the main goals for teaching geography. As a result, the newly revised geography curriculum for upper secondary schools included four goals: landscape and climate, cultural landscape, resource and industry, and population and settlement (Sætre, 2016, p. 73).

Topics related to EE and ESD tend to be more prominent within Norwegian curricula compared to ones used in Ontario. However, support for integrating ESD within school systems in Norway does not stop there. A program called “The Sustainable Backpack” has been implemented in approximately 600 primary, lower secondary and upper secondary schools in Norway. This initiative allows schools to gain the financial aid they need to implement EE and ESD within their school community, which includes and is not limited to: teacher training, curriculum planning, school projects, and external collaborations (One Planet, 2018). Due to their efforts, “The Sustainable Backpack” ended up producing “more environmentally conscious students” (One Planet, 2018). With ESD becoming increasingly relevant, the program plans on improving their approach to educating teachers about ESD in hopes that “all teachers will be able to participate in sustainable development courses” in the near future (One Planet, 2018). Based on the given information, EE had a prominent place within Norwegian curricula before being slowly replaced by ESD. With the revision of the geography curriculum (to one that emphasizes the importance of sustainable development) and the rise of support initiatives like “The Sustainable Backpack” program, Norway has demonstrated the incentive needed to implement ESD in their school systems and curricula. Even so, exactly what factors come into play when it comes to integrating ESD in both Ontario and Norway?

Factors that Influence the Integration of ESD

Social and Economic Factors in Ontario

When considering the implementation of ESD into Ontario and Norwegian curricula, exploring the social and economic factors of each country are necessary in understanding how environmentalism and sustainability has and is being integrated, and why. Social factors influence groups by dictating what is the norm, and affect the individual lifestyles of peoples in a given population. Combined with economic factors, ESD is determined by the social values of the population, and the economic factors that affect local environment and sustainability. One major social factor of a population is identity. Canadian identity is vastly built on the diversity of the land and of the people. Borris Vormann and Christian Lammert (2014, p. 308) argue that “regionalism” has historically been a key feature of Canadian civic nationalism, and exists in Canada because of a “lack of a national civic religion, inspirational leaders and ideologists through history” that has failed to create a unified national identity. The vastness of Canadian geography and the different ethno-cultural groups that have historically settled and lived in these different geographic locations has caused regionalism to be “a main cultural and socio-economic fact of Canadian life” (Ibid., p.308). As a result, modern Canadian identity reflects a mosaic, where minority and disparate cultural and ethnic groups are celebrated and Canadians pride themselves on a culture of inclusiveness and diversity (Taub, 2017). The cultural mosaic and the inherently inclusive perspective of the population reflects a politically liberalistic perspective, but the regionalistic influence has created a diverse political spectrum that varies across the left-right dimensions.

Implementation of environmental policy and ESD in schools has been made complicated because of this varied political spectrum. Canada is a major contributor in global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Based on data provided by the International Energy Agency, the Union of Concerned Scientists ranks Canada 11th overall for the top 20 countries that emitted the most carbon dioxide in 2018, at 0.56 metric gigatons. Per capita, that places the country 5th overall at 15.32 metric tons (Union of Concerned Scientists, 2018). In 2015, Canada agreed to join the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which presented a set of 17 global goals and 169 associated targets. Canada presented a Voluntary Review (2018) for the 2030 Agenda, where the country states its determination to reduce GHG emissions by 30% by 2030, and discusses the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change (2016) implemented under the Liberal federal government. As the first climate change plan in Canada’s history to include collective and individual commitments of federal, provincial and territorial governments, it includes 50+ concrete measures to reduce carbon pollution, build resilience to the impacts of climate change, foster cleantech solutions and create good jobs that contribute to a strong economy.

The country’s largely liberalist identity reflects the importance placed on sustainability and environment on a global scale, but the implementation of sustainable development goals on a national level is challenged by the opposing Liberal and Conservative political parties. On a federal level, the Liberal government prioritizes climate policy through setting net-zero emissions goals, green investments, and a national carbon tax. The Conservatives on the other hand do not believe in policies that impact climate change, and instead rely on tax incentives to support technological development that back energy efficiency (McCarthy & Walsh, 2019). The differing approaches to environmental sustainability and combating climate change make it difficult for one method to remain consistent over years and different federal governments. If the Liberal party implements policies, the Conservatives will revoke it and focus on tax incentives. The cycle goes on, and an accepted consensus is hardly achieved. This is also reflected at a provincial level, as importance on different educational philosophies changes based on who sits in the Premier’s office. The Conservative government tends to focus on traditional practical skills, reflected in the recent importance placed on literacy and numeracy. Environmentalism and sustainable practices are not seen as important, thus why the curriculum lacks a solid base or framework for ESD. Frameworks in curricula reflect citizenship and democratic practices instead of ESD, and teaching environmentalism and climate policy is placed primarily in the hands of teachers willing to take it on in practice.

Social and Economic Factors in Norway

Identity in Norway is based on the idea of friluftsliv, which loosely translates to “outdoor life”. Termed by a Norwegian playwright in the 19th century, friluftsliv describes a broadly recognized and valued concept that has historically valued spending time outdoors across the Norwegic region (Vegsund, 2018). Brooks and Dahl (Vegsund, 2018 p. 17) define it as “nature-life traditions” that “resemble oral tradition, kept alive by repetition and subtle improvisation in response to the patterns and variations in nature, encountered along well-known paths”. This in part is due to the geographic makeup of Norway, since only 1% of the country consists of urbanized areas. As a vastly rural population, “individuals have always used the environmental areas around them extensively; fjords, valleys, woods, jills, lakes and mountains for fishing, agriculture, forestry and mining” (Andersen & Wennevold, 1997, p. 157). Acknowledging this, it is easy to understand why place-based education and sustainable teaching is implemented as interdisciplinary practice. With such a high value and respect placed on the local environment, teaching outdoors and using geographic locations as a playground for learning is highly valued and practiced traditionally in Norwegian education.

Unlike Canada’s regional makeup, Norwegian identity is nationally based. This unified national identity is reflected in the country’s political environment as a primarily centralist and social state. With a smaller landmass and overall population, the political system does not have a seperate regionalistic system to enforce policy like Canada does. This makes it easier for the country to make changes to curriculum and education, as responsibility over education is not divided among different governing systems. Ranked by the Economist Intelligence Unit in 2017 as the best democracy in the world for 6 years running, Norway’s political system focuses more on the collaboration between parties to implement policies and procedures (as cited in Smith & Adams, 2017). The two main oppositions, Arbeiderpartiet (labour party with a liberal perspective) and Høyre (liberal-conservative) have traditionally gained the majority seats in the latest elections (Nikel, 2020). In 2019, climate change topped Norway’s annual list of important political issues of the populace for the first time ever. Gaute Eiterjord, leader of the environmental organization Natur og Ungdom (Berglund, 2019) stated that “I think this amounts to a clear message to all involved with climate issues, to sharpen up”. While the Greens Party supports environmental action the most, the Socialist Left Party looks to develop a center-left platform, and the Center Party will only cooperate with the Arbeiderpartiet. The Greens and the Center strongly disagree on most green issues, and the Center continues to face ongoing criticism that their actions are not “green enough” (Ibid., 2019).

Economically, Norway ranks quite low in developed countries for GHG emissions on a global scale. In 2019, the country’s global cumulative CO2 emissions only accounted for 0.16% annually (Ritchie & Roser, 2020). With the high importance put on outdoor life and the environment of the nation, Norway actively participates in many initiatives to reduce GHG emissions globally. Like Canada, Norway is participating in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and previously signed the Kyoto and Paris Agreements. On the 2030 Agenda, Norway is committed to reducing emissions by at least 40% by 2030, compared to their 1990 levels. In their progress report on the 2030 Agenda titled “One Year Closer” (Norwegian Ministry of Finance, 2019, p. 6), Prime Minister Solberg states that “at a time when we need more, not less, global cooperation, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is the roadmap that ensures everyone wins, even at the national level”. Implementation of environment and sustainable politics at the national scale continues to be better, as contesting parties work together to improve on the country’s environmental impact. Making changes of ESD within the education system is much easier, as the core curriculum elements in writing support any efforts schools and teachers make towards experiential outdoor learning and practices of sustainable teaching and learning. While economic policy and agendas concerning environmentalism and sustainability are still contested domestically, the general population’s recent importance put on climate change combined with a historically naturalistic identity allows Norway to socially and economically be a leading country in ESD teaching and environmental action and policy.

In conjunction to the information about EE and ESD within Ontario and Norwegian school systems and curricula, social and economic factors that influenced and is still influencing the integration of ESD, and modern-day teaching practices that currently exist and are popularized in both geographic regions, a brief study was done to accompany all that has been discussed. For this section of the study, focus was put on the perspectives of teacher candidates and teachers in Ontario and Norway. By interviewing and surveying teachers of various teaching specialities and experiences, further insight into teachers’ current knowledge about ESD, how ESD is being implemented into their schools and classrooms, and any limitations that currently exist were explored.

Participants

In total, 8 individuals have participated in our study. Unfortunately, due to the strict time constraint of having three weeks to finish this project, it was a challenge to find participants under short notice. In addition, permission was also granted from all contributors to incorporate their first name in this study. The following table below shows basic information about the individuals who were involved in this project (see Table 1).

Name or Pseudonym | Current Occupation | Experience (in years) | Sex | Nationality |

Abby | Teacher candidate | >2 | F | Canadian |

Allison | Teacher candidate | >2 | F | Canadian |

Nicole A | Teacher candidate | >2 | F | Canadian |

Nicole B | Secondary school teacher (Grades 9 to 12) | 10+ | F | Canadian |

Annveig | Primary school teacher (Grades 3 & 4) | 10+ | F | Norwegian |

Elin | Primary/Lower secondary school headmaster | 15+ | F | Norwegian |

John | Primary school teacher (Grade 1) | 10+ | M | Norwegian |

Nikolai | Lower secondary school teacher (Grades 8 & 10) | 4 | M | Norwegian |

Table 1. Basic information about each participant.

The Norwegian participants were chosen thanks to the help of Dr. Sørmo and her connections, whereas the Ontario participants were chosen based on their relations to the authors of this paper. In addition, it is important to note that the Ontario teacher candidates and certified teachers who participated in this study have experience in teaching either geography or the sciences; therefore, being more informed about the meaning of sustainability and sustainable development compared to those who may have had less or minimal exposure to ESD.

Design

For simplicity and efficiency, interviews and surveys were conducted for this study. As such, participants were provided either an interview or a Word document survey, or just a Google Forms survey depending on the medium that seemed to best fit their comfort and schedule. In terms of the contents of the interviews and surveys, the same questions were asked to all participants, as can be seen in the table below (see Table 2).

1 | Could you tell us what you currently know about sustainability and Education for Sustainable Development? |

2 | When going through “Teacher Education”, how much emphasis do they put on teaching sustainability or sustainable development? If any at all. |

3 | Based on a teacher’s perspective, how important is teaching sustainable development? a) What sorts of topics do teachers tend to focus on? (e.g., environmental sustainability, resource sustainability, etc.) |

4 | According to the new curriculum [in Norway], ESD is supposed to be interdisciplinary. Could you tell us what the term “interdisciplinary” means to you as a teacher? a) Do you think there should be a bigger presence of teaching sustainable development in schools? Or even in other subjects besides social science and natural science? |

5 | Climate change is an emerging topic of concern in teaching sustainability. Do you think climate change is being adequately addressed in your school and classrooms? |

6 | Do you think your students are gaining valuable insight on their individual roles within their environment and creating positive sustainable change and action? |

7 | If teaching sustainable development needs improvement, in your opinion, what do you think limitations are for you as an educator? What could be done or implemented to overcome these obstacles? |

Table 2. Questions asked during interviews and surveys.

Procedure

Within the second week of this project, teacher candidates, teachers, and headmasters were contacted in Ontario and Norway to see if they were willing to participate in the study. As aforementioned, due to time constraints, two main methods of data collection were constructed in order to gather qualitative data: an in-person interview through Zoom/Teams and a self-paced Word document/Google Forms survey. Before the creation of the online Google Forms survey, Norwegian candidates were provided a Word document with the questions from table 2 so that they were able to prepare ahead of time. In addition, teachers in Norway had the choice to either discuss with us via a video-conferencing platform or fill out the Word document that was sent to them earlier in the week. At the same time, participants in Ontario were strictly sent a Google Forms survey for easier data collection and organization. As a result, three interviews were conducted, one Word document was acquired, and four submissions were received from the survey. The data was then collected and organized into tables for easier analysis, which can be found in Appendix II.

The responses gathered from the interviewees and survey participants demonstrate that Norwegian and Ontario teachers largely understand what ESD and EE are and recognize it as a relevant and important practice in teaching. The results also display that teachers in both Norway and Canada identify gaps in curricula to support ESD and EE, as well as in varied practices of implementation based on individual interpretation of need as well as classroom, school, and regional environment.

Here is the summation of the following data gathered from each interview question:

- Could you tell us what you currently know about sustainability and Education for Sustainable Development (ESD)?

All interviewee’s responses highlight interacting with the environment as a key variable, as well as the impact of individuals on the environment. There was a focus on the lense of 21st century teaching, and the long lasting impact of individual actions today on the earth’s environment. John and Nicole B. both made a connection to ESD and the United Nations own initiative, discussing ESD as defined by the organization. The Norwegian educators also focused more deeply on the interaction between humans and the natural world, whereas this is demonstrated by the Ontario teachers as well, but Allison explicitly defined teaching sustainability as focusing on Indigenous ways of interacting with the environment. Elin indicates that the new 2020 Norwegian curriculum and it’s focus on sustainability reflects a national plan with key targets on renewable resources such as the ocean and food. In their response to this question, Nikolai also mentions the double moral of Norway’s economic prosperity and social value placed on sustainability, which can be connected back to the social and economic factors of Norway above. When asked this first question, all teachers were able to recognize and understand the term sustainability, some referring to the United Nations’ ESD initiative.

- When going through “Teacher Education”, how much emphasis do they put on teaching sustainability or sustainable development? If any at all.

The Ontario educators indicated having less exposure to learning about teaching sustainability and sustainable development in comparison to the Norwegian teachers. The exception would be Abby, who indicated there was an emphasis, and Allison, who indicated that their Biology and Chemistry teaching subjects for Intermediate/Senior qualifications has included significant exposure towards ESD and EE. All Norwegian educators mention sustainable practices taught in their teacher education program due to increased curriculum focus in schools. John indicates that while there was some, and that teaching sustainability and sustainable development was focused primarily in Geography and History, as well as included in the teaching of the culture of Norway’s Indigenous Sami people. Interviewees’ responses demonstrate that teachers who specialized in teaching the Sciences have had more exposure to sustainability and environmentalism as compared to those who specialized in Geography or Arts. When it comes to teaching geography specifically in Ontario, focus is put on the physical and human aspect of Canadian geography rather than environmental education (although there is still a small presence of EE and ESD within the Ontario geography curriculum). Elin states something similar, indicating that was not as it is now and there was not enough focus in Arts and Languages.

- Based on a teacher’s perspective, how important is teaching sustainable development? (a) What sorts of topics do teachers tend to focus on? (e.g., environmental sustainability, resource sustainability, etc.)

All interviewees’ responses agreed that teaching Sustainable Development is important. The Ontario educators indicated that environmental sustainability/climate action, resource sustainability, and clean energy are topics of focus. Allison again mentions Indigenous Education, and Nicole A. highlighted poverty as an additional topic of importance. Norwegian educators mentioned recycling, resource management, climate action, and environmental sustainability/nature preservation. Annveig identifies social sustainability as a key focus topic, and Nikolai mentions community infrastructure as another focus in their teaching. Nikolai also indicates in their response that Norwegian teachers have a lot of flexibility in focus topics, as long as it fits into the new core curriculum. While positive, Nikolai explains how lack of resources and outdated textbooks make teaching sustainable development a harder task. Both John and Nikolai indicate that the recent and frequent curriculum revisions have created challenges for teachers new and old and made it difficult to keep up practices and resources with current curriculum standards.

- According to the new curriculum [in Norway], ESD is supposed to be interdisciplinary. Could you tell us what the term “interdisciplinary” means to you as a teacher? (a) Do you think there should be a bigger presence of teaching sustainable development in schools? Or even in other subjects besides social science and natural science?

All interviewees understand interdisciplinary as teaching different topics and curriculum goals across multiple subject fields. Both Ontario and Norwegian educators believe there should be a larger presence of teaching sustainable development within their respective regions, and agree ESD should be incorporated into more subjects. Specifically in Ontario, the lack of ESD in the curricula could account for the need for a larger presence of ESD. Whereas in Norway, the need for ESD can be linked back to national identity which is heavily influenced by environmental and outdoor life as well as traditions. In fact, John mentions the importance of analysing social and cultural traditions and integrating this into teaching, and describes teaching subjects more as being integrated into “themes”, that of which the subjects can be fit into. Elin indicates that pupils seem to be learning better with interdisciplinary teaching, and that it incorporates the unique interests and skills of students better. Nicole B. explains that there is a lack of depth in teaching ESD cross-curricularly in Ontario schools, and maintains that ESD is not fully interdisciplinary across all subjects, and that it is especially not taught in compulsory courses. Alternatively, Nicole B. does mention the extra-curricular programs, teams and clubs that exist outside of the classroom where students do get the chance to participate in ESD. Regardless of the country, ESD is heavily reliant on teacher and school initiative. The curriculum cannot force teachers to implement ESD into their lessons. As such, teachers must work together to integrate ESD and have the desire to achieve a successful outcome.

- Climate change is an emerging topic of concern in teaching sustainability. Do you think climate change is being adequately addressed in your school and classrooms?

Ontario educators are mixed as to whether they believe climate change is being adequately addressed in the classroom. Abby believes it is, while Allison agrees somewhat, but recognizes she only has experience from the Science subjects. Nicole A. and Nicole B. both agree that it is not being adequately addressed. Elin, Annveig, John and Nikolai agree that climate change is being addressed in schools, but John and Nikolai both conclude that there is still not enough awareness and that it can still be taught more as one of the biggest issues of our future. All educators recognize climate change as a large issue and agree that it is important to address in all classrooms and schools.

- Do you think your students are gaining valuable insight on their individual roles within their environment and creating positive sustainable change and action?

Interviewees provide mixed responses to this question. The general consensus is that teaching students their individual roles within climate action is important, but there are different ideas on how well students understand their responsibilities as individuals. This largely depends on the subject and grade level that the educator is teaching. Abby believes students do, Allison mentions that they do try to incorporate as much information on student roles as they can, while Nicole A. says that they are not motivated and do not have the proper education to make change. Nicole states that students recognize their impact, but as a result of the teachers personal interest in these topics. Elin indicates that they hope students do. John says it is hard to tell at their age, but Annveig and Nikolai both agree that students do seem to understand their actions and impact on climate change. Annveig, like Nicole A. agrees that there can be problems with motivation, doubting that students are willing to reduce their living standards in order to make a change. In addition, Nikolai states that creating positive sustainable change is one of the main goals of the Norwegian education system. Thus, there has been an increase in implementing ESD related topics so that students are aware of their environmental presence. Unlike in Norway, it is mainly up to educators to introduce ESD related topics to their students. In doing so, the students themselves have the necessary knowledge and tools to reduce their ecological footprint on their own terms.

- If teaching sustainable development needs improvement, in your opinion, what do you think limitations are for you as an educator? What could be done or implemented to overcome these obstacles?

All interviewees recognize limitations in implementing ESD into schools in both Norway and Ontario. Teachers in Ontario describe limitations such as a lack of resources, open-endedness of the curriculum, lack of direction for educators, and lack of time. Norwegian educators indicate that limitations exist in lack of knowledge and community coherency (ability for educators to work together to create content and lessons), funding, school management initiatives, lack of interdisciplinary knowledge regarding ESD teaching, and again lack of time. Some educators have a difficult time answering what can be done to overcome these obstacles and recognize it as a complex issue. Interviewees mention possible solutions of providing more and better resources, funding, increased salary for educators, providing realistic problems to students/better assignments, increasing teacher’s knowledge, and increased action through principals, schools boards and governments.

The current Ontario curriculum: in support or a hindrance to ESD.

The Ontario curriculum documents lack a lot in detail when addressing ESD. As mentioned and identified by interviewees, what is included in the curriculum regarding EE and ESD is minimal, and fails to guide teachers in how to implement these ideas into practice. The Ontario Ministry of Education (OME) formed the Working Group on Environmental Education who released Shaping Our Schools, Shaping Our Future in 2007 (The Bonder Report) which detailed the existence of EE and ESD in Ontario curricula. The report concluded that only a small proportion of curricula at the secondary level have content related to EE expectations, and the material that is there is optional. When looking at courses such as CGC1P/CGC1D that are mandatory for all students, that missing aspects of “how” is where EE and ESD would be. Bardecki and McCarthy (2020) outline how ESD contests traditional pedagogical practices and curriculum expectations, which makes it harder to implement it in the education system. Stevenson (Bardecki & McCarthy, 2020, p. 120) states that EE and ESD “stresses cooperative and collaborative strategies with an emphasis on creative and critical thinking”, where education right now is focused on content-based learning, and therefore individual progress and achievement. Traditional schooling also focuses on “high-status” knowledge, or largely rational and technically based learning. EE and ESD goes against that traditional knowledge set, as it accommodates other knowledges and encourages new ways of pedagogical practice in Ontario curricula.

ESD is also fundamentally interdisciplinary, which the Ontario curriculum is not. It demands a “whole school approach” where every member of the school community, from the students to the administrative staff, must work together to implement environmental practices into teaching and learning (Ibid., p.120). Teaching is not an independent profession, rather a job where educators work together to teach curricula. This works well for ESD especially at the elementary level and within departments at the secondary level, since teachers must work collaboratively in teaching specific subjects. Where EE and ESD meet obstacles in Ontario curriculum is in the interdisciplinary aspect that demands teachers to work together across subjects and teaching practices. At the secondary level especially, lack of collaboration between departments required for the successful implementation of EE and ESD is seen as the major issue by many educational experts (Ibid., 2020). The Bonder Report paved the way for the document released by the OME in 2009 called the Acting Today, Shaping Tomorrow which outlined a policy framework for EE in Ontario schools. The document echoes the Bonder Report’s statement that Ontario’s education system should be preparing students with the “knowledge, skills, perspectives, and practices they need to be environmentally responsible citizens” and stresses the education system’s responsibility in ensuring students understand their environmental responsibility and the connection they have between all living things (OME, 2009, p. 6). Despite this recognition, the actions the OME promises to complete to reach their strategies do not go deep enough to create meaningful change. Today this lack of longstanding action still reflects minimal expectations in curricula, absence of EE electives offered in schools, and continued focus on traditional, single subject-based teaching. This demonstrates how the Ontario curriculum continues to hold ESD back from student learning and engagement in the public school system.

The current Norwegian curriculum: in support or a hindrance to ESD

In comparison to the Ontario curriculum, Norway’s implementation of EE and ESD is addressed to a much higher degree and level of competency. The recently revised and implemented core curriculum introduced in August 2020 has 3 main elements, and in element #2 “principles for education and all-round development”, sustainable development has its own subsection under the interdisciplinary topics expected to be taught across grades 1 through 10 (UDIR, 2020). ESD is implemented directly into the schools through this, as teachers are responsible to use the expectations of the core curriculum and these interdisciplinary themes across all subjects. As the curriculum states, “sustainable development is about protecting life on earth and taking care of the needs of people living today, without destroying the ability of future generations to meet their needs” (Ibid., section 2.5.3). The goal of this interdisciplinary subject is for students to develop the necessary skills to make conscious environmental decisions with the understanding that their actions will have a continuous, future impact on the environment and the world. The importance placed on ESD in the new curriculum is effectively possible because of the larger interdisciplinary nature of Norwegian teaching practices, as recognized by interviewees, as well as the high importance and value placed on the environment and outdoor traditions that have existed culturally in the society’s identity for generations. As stated by the United Nations on Partnership for Change: Education (n.d.), environmental studies in schools has traditionally been a compulsory part of education in Norway. Through EE, students are given the opportunity to obtain the “knowledge, attitudes and skills” required for them to properly contribute towards further goals of sustainable development (United Nations, n.d.).

While the curriculum today demonstrates considerable attention paid to ESD and EE, it has not always been this way. In 2005, the Environmental Education in the North (Witoszek, 2018) completed research where they found that sustainability as a topic in schools was still seen as controversial to teach. As EE and ESD is a newer addition to standardized curricula across the country, resources and the essential teaching practices needed to fully implement it into teaching are not yet there. Nina Witoszek (2018) outlines how the Norwegian curriculum reflects a high degree of importance placed on EE and ESD, while at the same time there is a cultivated cognitive dissonance accepting the country as a ‘virtuous’ oil economy. This tension between ESD and the economic reality of Norway makes for a paradoxical relationship where cognitive recognition is needed for Norwegians to understand their current place and impact on environmental issues and change. Popularized textbooks used in schools fail to identify Norway as both an environmentally conscious country as well as a prosperous oil economy. They tend to address either the social or economic aspects of environmentalism, sustainability and the Norwegian economy, but often fail to make the ESD connection to pull the social and economic together. In the textbook Natural Science Level 8-10 from the popular Tellus series (2007, 2015), Norway’s extraction of oil and gas is framed in largely positive terms’ (Ibid., 2018). While this textbook discusses the process of oil extraction as a largely positive action, it briefly touches on the negative environmental impact, but fails to thoroughly address the dichotomy between the oil sector and it’s negative impacts on the environment and what students can do as active citizens to address these issues. The new core curriculum provides the framework for educators to work with ESD and creates opportunities for students to be agents of change, but resources are few and far between because this cognitive recognition and the core curriculum expectations are both so new. As teachers work together over the next few years to rework Norwegian classrooms to fit the new curriculum, the implementation of ESD will only improve over time.

Teaching practices that currently exist and are popularized in Ontario schools

Placed-based education (PBE), also commonly known as place-based learning (PBL), has gained traction in schools across Canada, including Ontario. Essentially, PBE is a “student-centered form of learning that heavily emphasizes inquiry into topics of importance in the community and “often occurs when performing exploration of the environment” (Loveless, 2021). In Canada, PBE is a method of practice that has no direct correlation to Ontario curricula. As such, implementing PBE in schools and classrooms ultimately depends on school boards, principles, and/or teachers, but it is not strictly restricted to a classroom setting; educational practices such as PBE can also be adopted as a whole-school approach. An example of this is the Teton Science Schools (TSS) located in Wyoming and Idaho, United States of America. These particular schools provide authentic, meaningful and engaging lessons for all students based on the geographic location of the school. As a result, the Teton Science Schools focus on three major factors: the environment, the local community, and the culture, in hopes that students will build various skills, value contribution and develop appreciation to the local environment. Schools such as the TSS demonstrate that it is possible to fully integrate ESD and PBE within a school system.

When it comes to the specifics of PBE, the pedagogical approach includes providing students a voice in what they are learning, how they are learning the materials and where they want to learn. Tailored learning ensures that all students’ needs and abilities are met, while also providing an equitable foundation where students can build up their current level of knowledge. In practice, PBE is known for its interdisciplinary nature and focus on sustainability of life (Promise of Place, n.d.). Moreover, students within a PBE system end up developing their comprehension and reflection skills since they are required to think critically and reflectively on various pressing topics from different perspectives. Through the skill development approach that comes with PBE, schools contribute to citizenship education across the curriculum. For example, teaching students to read, write and communicate through numerous forms; including civic projects where students engage in civic writing and speaking, ultimately developing students’ values and attitudes towards various issues in our world (People for Education, 2014).

Specifically to Ontario, teachers have developed substantial teaching and learning opportunities across the province that incorporate EE and/or ESD. However, there are many obstacles that comes with its incorporation, many of which interviewees identified, such as: overcrowded curriculum, time constraints, preference on literacy and numeracy, coherence across leadership on EE and ESD development, and level of expertise and comfort among teachers in their abilities to integrate EE and ESD in course curricula (Bardecki & McCarthy, 2020, p. 121). In fact, Bardecki and McCarthy (2020, p. 121) noted that with the absence of EE as a recognized teaching subject, very few teachers identify as “environmental educators”, outside of those who are involved in Specialist High Skills Major programs related to the environment. Even though time for teachers to develop resources and practices is limited, there are various resources and institutions available for teachers, such as: Ontario EcoSchools, Learning for a Sustainable Future, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, The Environmental Literacy Council, Green Teacher, local conservation authorities, the Ontario Society for Environmental Education, Ducks Unlimited, Evergreen, and WWF-Canada. In addition, there are online resources pertaining to place-based education that teachers can easily access in order to gain better insight into how PBE works in an environmental context. An example is Edutopia’s webpage on “Place-Based Learning”, which includes the following articles: “7 Tips for Moving Learning Outside”, “Bringing Core Content to Life with Outdoor Education”, “Moving from the Comfort Zone to the Challenging Zone”, Simple Ways to Bring Learning Outside”, and many others (Edutopia, 2021). With the recognition of EE and ESD comes the popularization of PBE in Ontario. Although changing current teaching practices is not an easy feat by any means, through the implementation of additional teaching practices connected to ESD, both teachers and students will be able to obtain valuable information and skills needed to become sustainable citizens.

Teaching practices that currently exist and are popularized in Norwegian schools

PBE is a major aspect of the education system when discussing current practices of teaching in Norway. Similar to Canadian teaching practices in that it is highly popularized, Norway’s education system integrates PBE more effectively across curriculum documents. PBE is highly valued in practice because of the importance put on outdoor play and learning. Britt Vegsund (2018, p. 7) says that the outdoor environment in Norwegian education is “both designed to encourage physically active play and used by educators as an arena for physically active play and learning”. For example, the curriculum demands that a specific amount of hours have to be dedicated to outdoor education and physical activity. Outdoor activity and PBE practices are naturally a huge part of the Norwegian education system, and contribute to the overall high importance put on EE and ESD. The interdisciplinary nature of the new core curriculum also demonstrates a high importance of PBE practice placed in education. In section 2.3 (UDIR, 2020) the curriculum outlines the 5 basic skills of reading, writing, arithmetic, oral skills and digital skills and stresses that teachers must make connections to these 5 basic skills across subject curricula. These skills are notably regarded as “important for the development of students’ identity and social relationships, and for being able to participate in education, work, and community life” (Ibid., 2020). Since the curriculum is so broad, it is up to individual schools and teachers to decide how they want to meet the given expectations. The broadness in the curriculum and the subsequent social value placed on being outdoors has resulted in a larger influence of EE on teaching over time, as interviewees have stated. In the Framework Plan for Kindergartens (2017, p. 52), it emphasizes how “Kindergartens shall enable the children to appreciate nature and have outdoor experiences that teach them to move around and spend time outdoors during the different seasons”. Regardless of the class or the subject, spending time outdoors is socially and culturally valued. It is because of this that EE and PBL occur simultaneously in the Norwegian curriculum.

Across the country, some of Norway’s top stakeholders and groups for sustainable development and environmental consciousness have created a variety of resources for educators to use. The Sustainable Backpack program is one that has already been mentioned, but there exists still a wide variety of additional digital tools for teachers to use as packages for lessons or even entire units that incorporate PBE practice in teaching EE and ESD. Many schools set aside their own funding for EE and ESD learning opportunities, as well as municipalities and the Norwegian government contribute to funding these teaching practices. Funding provided by external sources allows schools and teachers to partake in a variety of EE and ESD based programs that are currently running across the country. Natufag.no (2020) is a website developed by the National Center for Science in Education, and provides Norwegian teachers with a variety of EE and ESD resources for students at the primary level. These resources not only include activities and lessons, but opportunities for teachers to work on professional development and learn about different practices and methods of teaching EE and ESD. Another popular resource is Miljolare (n.d.), a website launched by the Environmental Education Network in Norway which works as a tool for training teachers and students in sustainable development. It offers an extensive list of activities to be carried out in schools’ local environments where observation and data collection can be shared and compared. However, many resources available to teachers only focus on the environmental side of sustainability, and do not necessarily connect to the other strands of ESD that look at individual responsibility in the community in ways that touch on subjects like poverty and inequality. This and the continued work of teachers and educational stakeholders required to restructure the school system with the new curricula demonstrates popularized use of PBE and EE practices, and a growing focus on ESD in Norwegian schools and classrooms.

This comparative research project has revealed many parallels as well as distinctive differences between the Ontario and Norwegian education systems. Globally, society is in a period of rapid change, increasingly so concerning the environmental status of the Earth. Living in the age of the Anthropocene, individuals now are forced to consider their environmental impact not only on a micro scale, but also from a globally minded perspective. Understanding what sustainable development is is integral to contextualizing the human impact on the environment and the Earth’s climate, as well as individual and group impacts on society, environment, culture, and economy. The United Nations effort to focus on Education for Sustainable Development, as well as other emphasis put on environmental education and place-based education in both Norwegian and Ontario school demonstrates an increasing demand and need for students living in the twenty-first century world to fully comprehend the current geological epoch, and be able to take effective action to alter the current course for the betterment of future generations to come.

The need and recognition of the importance of ESD, EE AND PBE is represented both in the Ontario and Norwegian curricula, but to different degrees of urgency. In Ontario, the resource guide Environmental Education outlines how topics of EE and sustainability should be incorporated into subject curricula, and even provides a few tips and tricks into how teachers should be going about doing it. The main issue with the Ontario curriculum is that there is an enormous lack of EE and ESD teaching implemented into the text and expectations. Grade 9 Geography (CGC1P/1D) is the only mandatory Intermediate level course that provides students with exposure. There are an additional few elective courses that focus on topics of EE and touch on topics of ESD, but the actuality of schools running these courses is extremely rare. There just are not the teachers who feel comfortable enough or trained well enough to take on these heavily focused ESD courses. In Norway, there is a completely different amount of emphasis placed on ESD teaching. The newly revised 2020 core curriculum includes sustainable development as one of the main pillars. Additionally, the curriculum is designed with interdisciplinary teaching as a main focus. With ESD being a broadly interdisciplinary topic, the Norwegian curriculum is set up to support instead of hinder ESD teaching. The lack of interdisciplinary focus is where Ontario curricula lags behind in this aspect. Additionally, in comparison to Ontario’s grade 9 compulsory grade 9 Geography course, the Norwegian upper secondary level Geography includes 4 main ESD based goals: landscape and climate, cultural landscape, resource and industry, and population and settlement. In the case of curricula, Norway far outmatches the goals of ESD education and curricula that Ontario is only just beginning to touch on.

Concerning popularized teaching practice, both Norwegian and Ontario educators understand the importance of and have a goal to include more ESD topics and teachings into their individual classroom environments, regardless of the classroom or course subject. With ESD being fundamentally interdisciplinary, Ontario teachers -especially Intermediate/Senior educators- have a difficult time implementing it into their teaching when the curriculum is not. Various resources for the classroom as well as school environments exist to support teachers in implementing ESD, but the curriculum is already overcrowded as it is. There are several constraints put on and felt by educators, and the large precedent given to numeracy and literacy skills overshadows any efforts to include much else. Therefore ESD education more often than not occurs outside the classroom and within the larger school setting, in specialized programs, clubs, activities and extracurriculars shepherded by teachers on their own time. In Norway, teachers are given more of an opportunity to work with ESD in the broader curriculum with a much heavier focus on interdisciplinary practice. Many classes at various grade levels spend significant time learning outdoors, but it is always ultimately up to each individual teacher’s own initiatives and abilities to fully engage with ESD teaching practice. Like in Ontario, various resources exist for teachers to engage with more ESD material and teaching practices. The challenge lies for Norwegian teachers in keeping up with the changing core curriculum, and finding new ways to adapt their teaching and find resources to be able to fully engage with the ESD topics present in the revised curriculum today.

Various economic and social factors in both Ontario and Norway affect the ways in which ESD is implemented into curriculum and practice. From research, interesting findings between the countries’ relationships with their own climate impact and their education system and philosophies unveils an interesting dichotomy that exists between society and the increased importance of ESD content and practice. The continued lack of ESD in Ontario schools can be accredited to a divided regionalistic identity, the multitude of involvement of different political entities, and an economic sphere with a massive impact on the world’s GHG emissions. Norway’s own GHG emissions and reliance on an oil-based economy would potentially indicate a similar situation as in Ontario, but the larger national identity of friluftsliv and high importance placed on outdoor life creates a realm of increased need of ESD, EE and climate saving practices within society and government. While these various factors, the state of curricula and teaching practice in both countries, and the accounts given by interviewees provide a better understanding of the differences between Ontario and Norwegian public educational emphasis placed on ESD, it also reveals a parallel between both countries across the Atlantic. ESD is important, and understanding the definition and purpose of sustainability is essential for students to know. There may be various limiting factors that make it difficult for educators to focus on these topics of the environment, but educators are doing the best that they can with what they’ve got to make informed choices, teach students topics of ESD, and provide them with opportunities to take action and better understand their individual responsibilities as people of a global world. It is a changing world, and like always, teachers continue to develop professionally, adapt, and overcome to do what is best for generations to come.

This research project was possible thanks to organizations and individuals who have provided us assistance throughout the last several weeks. We would like to give sincere thanks to our project supervisor, Wenche Sørmo, and her colleagues, Karin Stoll and Mette Gårdvik, for guiding us on this journey. Thanks to our supervisors from Nord University, we were able to learn more about sustainability and ESD in Norway, were able to interview Norwegian teachers, and were able to receive the guidance needed to write a formal research paper. We also thank our survey participants for taking the time out of their busy schedule to answer questions for our research: Abby, Allison, Annveig, John, Nicole, Nicole, Elin and Nikolai. With the short notice that they had, their insight was highly valuable to us and we could not have finished our research without them. Lastly, many thanks to the CANOPY team, Nord University Faculty of Education and Arts, and Queen’s University Faculty of Education for allowing us to take on this project for our alternative practicum at Queen’s University. Without our FOCI course professor, Dr. Chin, and her course assistant, Raquel, we would not have been aware of this opportunity. The help that we received from everyone throughout this process has been and still is greatly appreciated and without them, our final product would not have been possible.

Andersen, H. P., & Wennevold, S. (1997). Environmental education in Norway – Some problems seen from the geographer’s point of view. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 6(2), 157–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.1997.9965041.

Bardecki, M. J., & McCarthy, L. H. (2020). Implementation of the Bondar Report: A reflection on the state of Environmental Education in Ontario. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 23(3), 113–131. https://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/article/view/1585.

Berglund, N. (2019, November 25). Climate change tops all political issues. News in English: Views and News from Norway. https://www.newsinenglish.no/2019/11/25/climate-tops-major-political-issues/.

CANOPY. (2021). The Canada-Norway Pedagogy Partnership for Innovation and Inclusion in Education. Nord University. https://blogg.nord.no/canopy/.

Cohen, B. J., & Rønning, W. (2017). Place-based learning: Making use of nature in the young children’s learning in rural areas of Norway and Scotland. Cad. Cedes, 37(103), 393–418. https://doi.org/10.1590/CC0101-32622017176129.

Edutopia. (2021). Place-Based Learning. Edutopia. https://www.edutopia.org/topic/place-based-learning.

Government of Canada. (2018). Canada’s implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: Voluntary national review. Global Affairs Canada. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/20033CanadasVoluntaryNationalReviewENv6.pdf.

Government of Canada. (2016). Pan-Canadian framework on clean grown and climate change: Canada’s plan to address climate change and grow the economy. Environment and Climate Change Canada. https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.828774/publication.html.

Loveless, B. (2021). Guide on place-based education. Education Corner. https://www.educationcorner.com/place-based-education-guide.html

McCarthy, S., & Walsh, M. (2019, October 12). Federal election 2019: Where the four main parties stand on climate policy. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/politics/article-federal-election-2019-where-the-four-main-parties-stand-on-climate/.

Miljolare. (n.d.). Current activities. Miljolare. https://www.miljolare.no/.

Munkebye, E., Scheie, E., Gabrielsen, A., Jordet, A., Misund, S., Nergård, T., & Øyehaug, A. B. (2020). Interdisciplinary primary school curriculum units for sustainable development. Environmental Education Research, 26(6), 795–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1750568.

Naturfagsenteret. (2015). The Sustainable backpack. https://www.natursekken.no/c1187999/artikkel/vis.html?tid=2104906.

Naturfagsenteret. (2020). Sustainable development. Naturfagsenteret. https://www.naturfag.no/tema/vis.html?tid=1994602.

Nayar, A. (2013, September 29). Importance of Education for Sustainable Development. World Wide Fund for Nature. https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?210950%2FImportance-of-Education-for-Sustainable-Development%2F.

Nikel, D. (2020, September 27). Political parties in Norway. Life in Norway. https://www.lifeinnorway.net/political-parties/.

Norwegian Ministry of Finance. (2019). One year closer 2019: Norway’s progress towards the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Report. Norwegian Ministry of Finance and Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/one-year-closer-2019/id2662712/.

OECD [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development]. (n.d.). Norway: Education for Sustainable Development – Flaktveit school, municipality of Bergen. http://www.oecd.org/education/ceri/49765675.pdf.

OME [Ontario Ministry of Education]. (2009). Acting today, shaping tomorrow: A policy framework for Environmental Education in Ontario schools. http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/teachers/enviroed/shapetomorrow.pdf.

OME [Ontario Ministry of Education]. (2015). The Ontario curriculum grades 11 and 12: Canadian and World Studies. http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/curriculum/secondary/canworld910curr2018.pdf.

OME [Ontario Ministry of Education]. (2017). The Ontario curriculum grades 1 – 8 and the Kindergarten Program – Environmental Education: Scope and sequence of expectations. http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/curriculum/elementary/environmental_ed_kto8_eng.pdf.

OME [Ontario Ministry of Education]. (2018). The Ontario curriculum grades 9 and 10: Canadian and World Studies. http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/curriculum/secondary/canworld910curr2018.pdf.

One Planet. (2018). The Sustainable Backpack. The One Planet Network. https://www.oneplanetnetwork.org/initiative/sustainable-backpack.

People for Education. (2014). Measuring What Matters: Citizenship Education. http://peopleforeducation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/MWM_CitizenshipSummary.pdf.

Promise of Place. (n.d.). Principles of Place-Based Education. https://promiseofplace.org/what-is-pbe/principles-of-place-based-education.

Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2020, June 11). Norway: CO2 Country Profile. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/co2/country/norway.

Sauvé, L. (1996). Environmental Education and sustainable development: A further appraisal. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 1(1), 7–34. https://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/article/view/490.

Study in Norway. (n.d.). Living in Norway – Education. https://www.studyinnorway.no/living-in-norway/education.

Sætre, P. J. (2016). Education for sustainable development in Norwegian geography curricula. Nordidactica: Journal of Humanities and Social Science Education, 6(1), 63–78. https://hvlopen.brage.unit.no/hvlopen-xmlui/handle/11250/2440437.

Taub, A. (2017, June 27). Canada’s secret to resisting the West’s populist wave. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/27/world/canada/canadas-secret-to-resisting-the-wests-populist-wave.html.

Teton Science Schools. (2021, January 21). Getting started with Place-Based Education, step-by-step. https://www.tetonscience.org/getting-started-with-place-based-education-step-by-step/.

UDIR [Ministry of Education and Research]. (2017). Framework Plan for the content and tasks of kindergartens. Utdanningsdirektoratet. https://www.udir.no/in-english/framework-plan-for-kindergartens/.

UDIR [Ministry of Education and Research]. (2020). Core curriculum – values and principles for primary and secondary education. Utdanningsdirektoratet. https://www.udir.no/lk20/overordnet-del/?lang=eng.

UNESCO. (2015). Sustainable Development. https://en.unesco.org/themes/education-sustainable-development/what-is-esd/sd.

UNESCO. (2017). Education for Sustainable Development Goals. Paris: UNESCO.

Union of Concerned Scientists. (2020, August). Each country’s share of CO2 emissions. https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/each-countrys-share-co2-emissions.

United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda.

United Nations. (n.d.). Partnership for Change: Education. https://www.un.org/esa/earthsummit/norway/english3.htm.

United Nations. (n.d.). Take action for the sustainable development goals – United

Nations sustainable development. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/.

Vegsund, B. (2018). Education on the move: Ideas and inspiration for school-based physical activity from Norway. http://southshoreconnect.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Education-on-the-Move.pdf.

Vormann, B., & Lammert, C. (2014). A paradoxical relationship? Regionalization and Canadian national identity. American Review of Canadian Studies, 44(4), 385–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/02722011.2014.973426.

Witoszek, N. (2018). Teaching sustainability in Norway, China and Ghana: Challenges to the UN programme. Environmental Education Research, 24(6), 831–844. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2017.1307944.

Appendix I. CANOPY Information Brochure

Appendix II. Results from Interviews and Surveys

Could you tell us what you currently know about sustainability and Education for Sustainable Development (ESD)? | |

Abby | I don’t know much about it |

Allison | Teaching sustainability has a great focus on indigenous ways of interacting with the environment. Sustainable education can also be paired with environmental education, outdoor education and many different curriculum subjects. |

Nicole (Teacher Candidate) | I know about the 17 goals for sustainable development. |

Nicole