This is a blog post written by our new PhD student, Charlotte Gehrke.

While some already call him a global icon, Volodymyr Zelenskyy remains a relatively new player on the international stage. Though many journalists and foreign policy experts outside of Ukraine have closely followed his political career since its early days in 2018, the international public’s awareness of the celebrity president is still young, and perceptions of Zelenskyy continue to evolve amid Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This blog post briefly summarizes the president’s origin story, how the broader international public first became acquainted with Zelenskyy, and his newfound status as a heroic international icon.

Origin Story

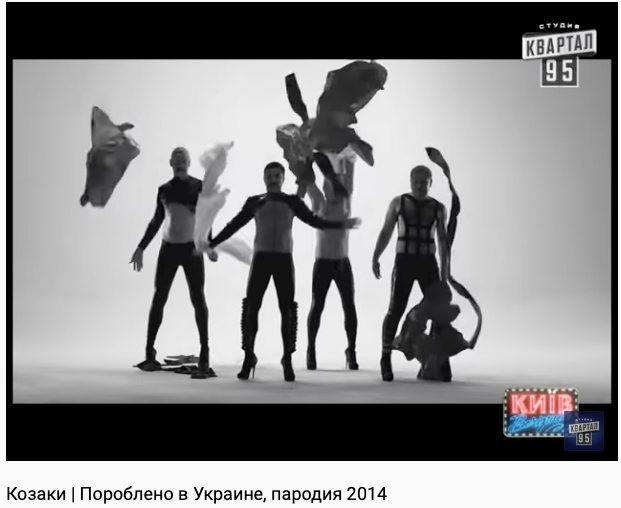

Born to engineer Rimma Zelenska and computer science professor Oleksandr Zelenskyy in 1978, Volodymyr Oleksandrovych Zelenskyy grew up as a native Russian speaker in the Ukrainian city of Kryvyi Rhi. A law graduate of the Kryvyi Rih Institute of Economics, Zelenskyy decided to join into the entertainment business instead. Initially he was part of the Kvartal 95 improv group (named after Quarter 95, the Kryvyi Rhi neighbourhood Zelenskyy grew up in), and would later act in movies like No Love in the City and 8 First Dates. Beginning in October 2015, Zelenskyy became the co-creator and star of his own tv show, playing a history teacher turned president after his rant about political corruption goes viral. The show was called Servant of the People. The same name would later be given to Zelenskyy’s political party, founded by the show’s creator team in 2018. Following a protest candidate style campaign partially orchestrated by members of the same team, the 44-year-old became the 6th president of Ukraine in 2019 with 73.17 percent of the vote.

Catching the Public Eye and Ear

In his first year in office, Zelenskyy garnered some attention for his comedic background. Most coverage, however, remained in line with typical coverage of presidential incumbents, running the gambit from Zelenskyy’s (in)ability to realize campaign promises to dropping poll numbers.

It wasn’t until the Ukrainian president became entangled with American politics that he garnered widespread international attention. In an interview with Marie Yovanovitch, Steven Colbert asked the former US ambassador, “What was the appeal of a comedian? How bad were things in the political landscape there that they went ‘Oh, let’s give the clown a try.’” Yovanovitch responded by pointing to similarities between Zelenskyy and former US president Donald Trump: a political outsider running as a protest candidate, whom the political establishment ridiculed and failed to take seriously.

It was also Zelenskyy’s connection to Trump that first caught the attention of the international public in what is now known as the “perfect” or the “I would like you to do us a favor, though” phone call. The so-called ‘Ukraine scandal’ emerged in 2019 when a whistleblower complaint claimed that in a phone call, then-president Trump attempted to pressure Zelenskyy to investigate his political rival, former vice president Joe Biden, and his son Hunter Biden by threatening to withhold $400 million in congressionally mandated military aid to Ukraine. While the aid funds were eventually released, the investigation into Trump’s misconduct that followed provided the basis for the first impeachment inquiry (the 45th president was convicted by the US House of Representatives but acquitted by the Senate). It also led to an exodus of US government experts on Russia and Ukraine who were dismissed by the Trump administration or left of their own volition. Nevertheless, experts have predicted that the Ukraine scandal “likely will become a minor footnote” in Zelenskyy’s story, like Zelenskyy and his top aid Sergey Shefir being named in the 2021 Pandora Papers, or the Ukrainian president’s ties to oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky (owner of 1+1, which aired Servant of the People).

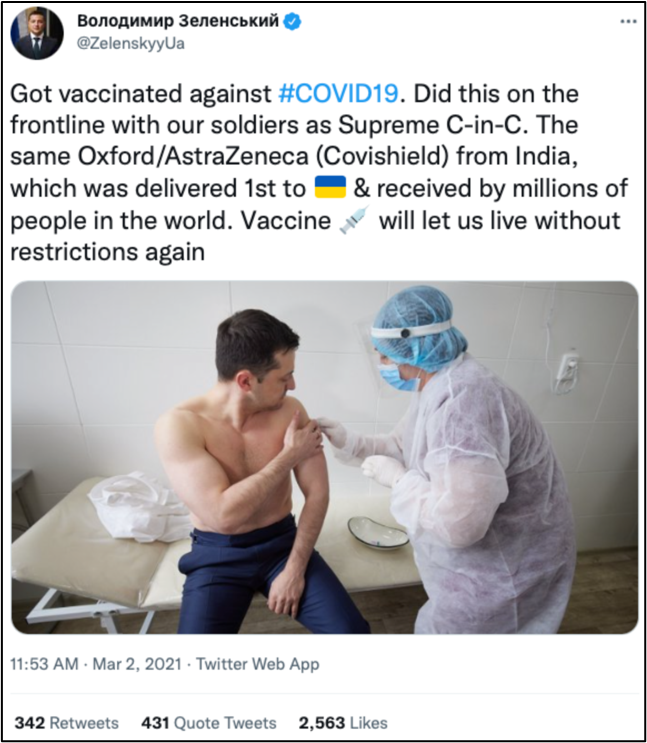

The following two years of Zelenskyy’s presidency would become defined by the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021, this allowed Zelenskyy to join the club of shirtless statesmen as pictures of his vaccination were widely shared.

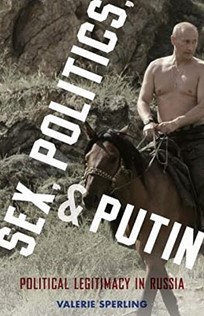

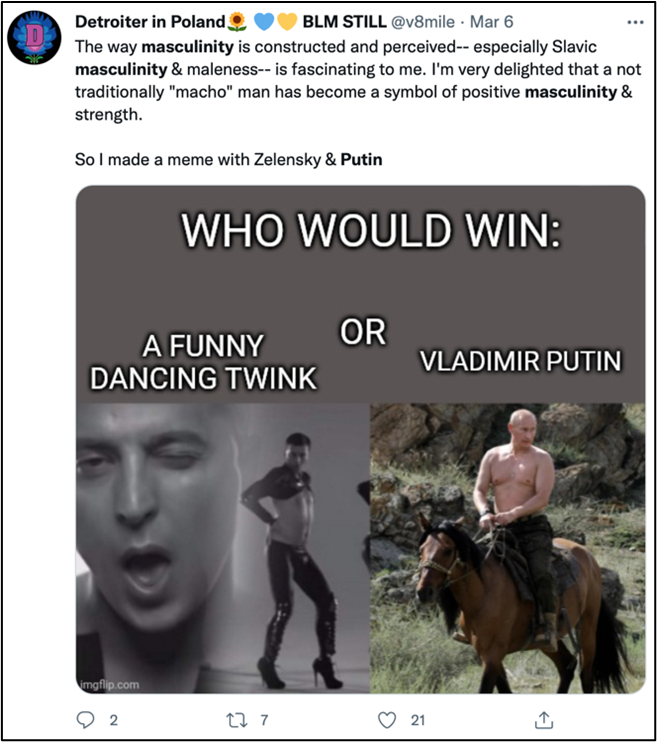

These images were also often contrasted with the hyper-masculine image that “has long been Russian President Vladimir Putin’s calling card,” from topless pictures of Putin riding horses or fishing to practicing martial arts, playing hockey, and shooting guns or rifles.

This comparison between the types of masculinity represented by Zelenskyy and Putin has taken on a new life amid Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, comparing Zelenskyy’s sense of self-humor and down-to-earth everyman appeal with Putin’s performance of masculinity, which is frequently interpreted as motivating his invasion of Ukraine.

While Zelenskyy once stated in an interview with The Times of Israel that “nobody cares” about his Jewish heritage, it took on new significance in light of Putin’s claim to pursue the “de-Nazification” of Ukraine. This provoked Zelenskyy to ask, “How could I be a Nazi?” citing his grandfather’s experience fighting the Nazis in World War II and three of his great-uncles being killed in the Holocaust.

International Icon

There have been many think pieces discussing the ways in which Zelenskyy’s background as a comedian and actor may have prepared and poised him for the leadership role he has assumed amidst Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. However, like other comedians-turned-politicians (such as former US Senator Al Franken) before him, Zelenskyy’s self-portrayal as a political candidate and president has largely been that of a serious leader and businessman. He has continued to project earnestness, stoicism, and bravery in his wartime leadership, being likened to Winston Churchill, whose 1940 ‘We Shall Fight On the Beaches’ speech Zelensky referenced in his recent address to the British House of Commons. When Zelenskyy reportedly replied to the US offer to evacuate him saying “I need ammunition, not a ride” the line became an instant rallying cry, meme, and even merchandise.

Nonetheless, with many in search of more lighthearted content, videos of Zelenskyy’s past entertainment work have gone viral, including comedy troupe performances of “Hava Nagila” and “Cossacks [Козаки],” appearances on Tantsi z zirkamy (the Ukrainian version of Strictly Come Dancing), and the animated film Paddington Bear (Zelenskyy voiced Paddington in the Ukrainian dubbed version).

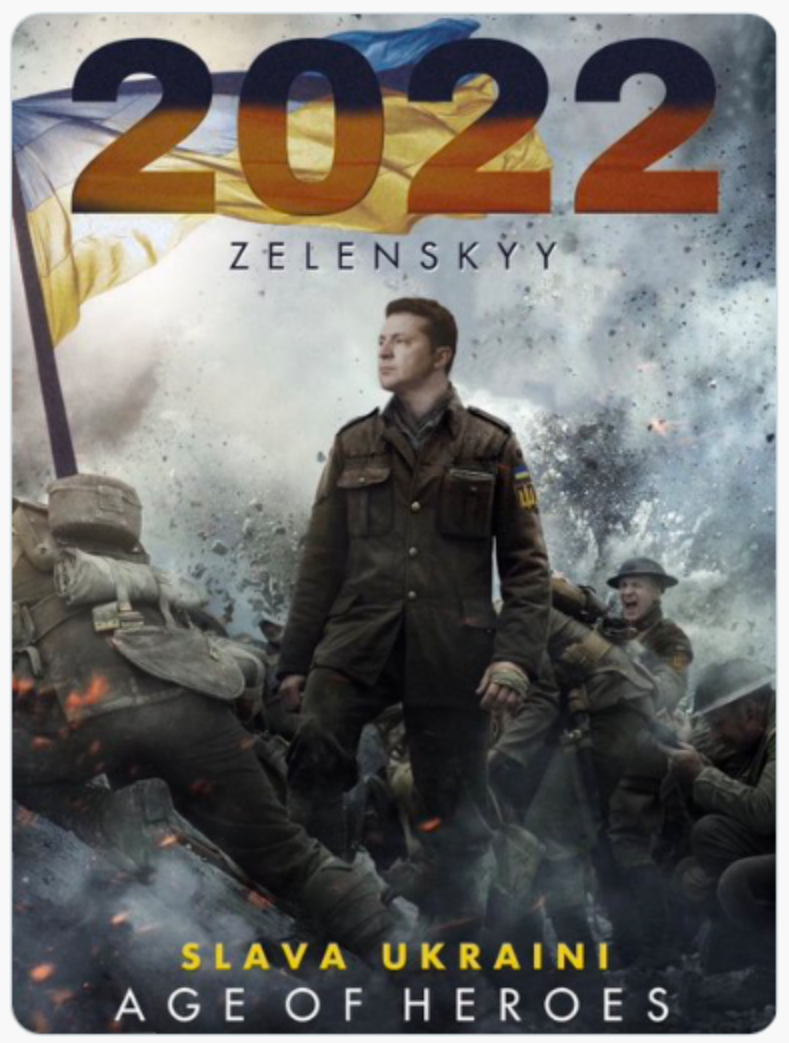

In this spirit of life imitating art, others have already begun to create art imitating life, including memes, fan art, and remixes of the president’s videos. As social media expert Ankana Susarla has noted, Zeleskyy’s ‘selfie videos’ have been particularly successful in conveying authenticity and connecting with social media users, as well as being vital assets in the ongoing information war.

International comedy icons have also paid tribute to the Zelenskyy, with Trevor Noah noting, “This man has more than stepped up to the crisis,” and Stephen Colbert telling his Late Night audience, “my new comedy idol is Volodymyr Zelenskyy… Normally, I am against electing comedians to political office… But this guy is inspiring the world with his courage in the face of the Russian invasion.” While the infectious courage of the Ukrainian population and president has already captured the international public’s attention, reports of officials mimicking Zelenskyy’s stoic everyman leadership have also begun to emerge.

As the first draft of history is being written, the ingenuity, sense of duty, and humor of the Ukrainian people continues to inspire the world and provide moments of joy and hope amid the terrors of war. Zelenskyy’s inclusion as part of this imaginative group of Ukrainian people speaks not just to his frequently described everyman persona, but rather the larger notion that “democracy does not need – and should not seek – the sorts of hero worship that authoritarians like Putin demand.”